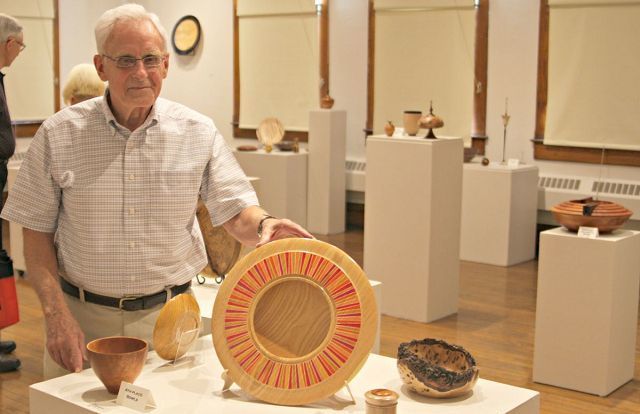

In Raeders hands, no such thing as just a piece of wood

There is art to be made from wood, even in its imperfections.

No one knows that better than George Raeder, who can read a piece of wood by just looking at it.

Theres the ambrosia maple, with its random sprinkling of pinpoint dark spots. It got its name, Raeder said, from the ambrosia beetles that infest it and leave their marks.

But its still a good canvas for a woodturner like Raeder, who came to the craft in the late 1990s after seeing a demonstration by Bert Marsh, a British master woodturner who died in 2011.

Raeder, who had experience as a woodworker, was inspired. I bought a lathe, bought some tools, he said. I had no idea what I was doing. He joined both the Buckeye Woodworkers and Woodturners and the North Coast Woodturners and went to work.

Years later, he woodturns and still does woodworking. Both skills bring him great satisfaction, he said, so I wouldnt classify one over the other.

But it is his woodturning that is currently on display as part of the Wayne Center for the Arts annual woodturners exhibition, which runs through Oct. 19 in the Looney Gallery. At the same time, the Gault Gallery is playing host to the annual exhibition of the Watercolor Guild.

While he built an addition to his home and has produced several pieces of furniture, Raeder said woodturning is in some ways more precise, often gratifying in the short term. A simple woodturning project might take a few hours; a simple bowl can be completed in five or six. Raeder has no set schedule, though he said he rarely works during the summer months, far preferring to spend his time outside.

By mid-October, Raeder said, he will be back in the 22-by-38-foot shop that was constructed along with his home in Bath Township, where he moved in 2012. Prior to that, he had a smaller shop at the Cuyahoga Fall home he shared with his wife, sculptor and master gardener Pat Raeder, who died in 2012.

Sometimes, he said, hell work a few hours a week. Other times, 10 hours a day. If I get enthusiastic about a project and really get going, he said, Im liable to work until 1 or 2 in the morning.

He will at times come up with the idea and finds the right wood for the job. But more often than not, he said, the wood dictates how the project moves forward. Its all about the shape, he said, and the imperfections. Raeder started with basic domestic woods walnut, maps, ash cherry. But he has branched out to more exotic species as well. Macasser ebony is an unbelievably beautiful wood, he said, as is cocobolo from South America. You have to recognize what the opportunities are that the wood has to offer, Raeder said. I rarely do the same thing twice.

And not every project goes as planned. Sometimes, the characteristic of a piece of wood necessitates course corrections. A mistake, Raeder said, is a design opportunity.

His concern is the quality of the finished project and hes a stickler for both technique and workmanship. Woodturning, he said, is not unlike golf. A beginner can improve quite a bit and fairly quickly but will hit a plateau where improvements are small and often unnoticed. Im always trying to improve my next pieces over the current one. In my view, there is no perfect piece; theres always room for improvement.

What visitors to the gallery will see is a beautiful collection of Raeders very best efforts. If I finish the piece and its not up to my standard, its a throwaway, he said. If my name goes on it, thats as well as I can do that piece.