Mt. Hope native played role in rise of electric vehicle

Energy storage has been around a very long time. In 1744 the Leyden jar was invented independently by Dutchmen Musschenbroek of Leyden, Holland and German scientist Ewald Georg von Kleist. They discovered a charge could be stored between two metal plates. In the 1760s Benjamin Franklin conducted experiments that proved Leyden jars could be ganged in parallel to store much greater charges. He named this device a battery.

The electric motor was invented by a Scottish Benedictine monk named Andrew Gordon in the 1740s. It was perfected over subsequent years by many.

These contemporaneous technologies were a natural combination. Electric vehicles were just a matter of time. Around 1835 Scottish inventor Robert Anderson created a carriage propelled by an electric motor. It was unfeasible as the batteries were not rechargeable. With the advent of rechargeable batteries around 1860, electric vehicles became much more practical. However, because most homes at the time were not electrified, battery charging was a challenge. The horse and buggy continued to be the preferred mode of transportation.

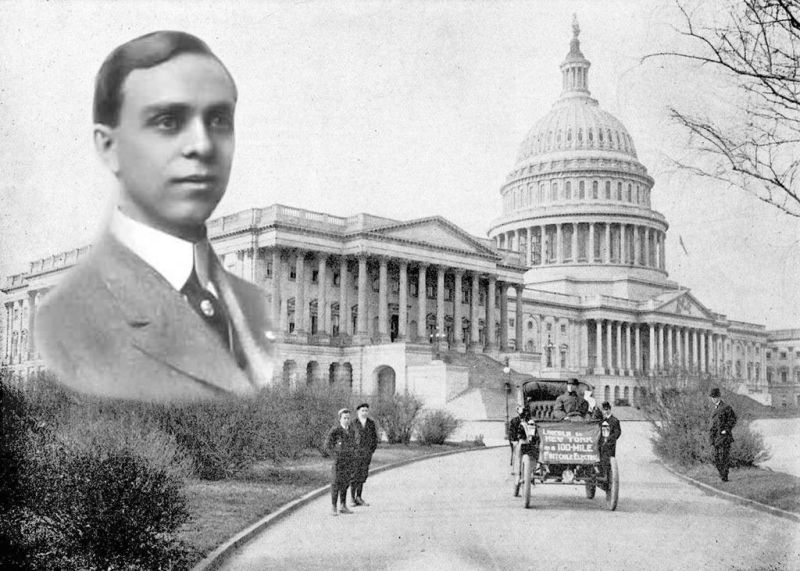

Oliver Parker Fritchle was born in Holmes County’s Mt. Hope on Sept. 15, 1874. He attended the local schools and graduated from Ohio Wesleyan University in 1896 with a BS in Chemistry. He worked for various metal and ore companies before receiving a patent for battery design in 1903 and starting his own business, Fritchle Automobile & Battery Company, in Denver in 1904.

One of his first designs reduced power consumption by half, almost doubling the range, relative to competitors’ vehicles. He also developed a controller that allowed his vehicles to use “electric brakes.” Today this is known as regenerative braking. The company’s first marketable automobile was the 1908 Victoria Phaeton, which Fritchle claimed could be driven 100 miles between battery charges.

To demonstrate the endurance claim, Fritchle issued an invitation to all electric vehicle manufacturers to join him in a rally from Denver to New York. Because of the lack of electrical infrastructure and the short notice, Fritchle had no takers. This may have been by design because Fritchle later used this in his firm’s advertising.

Fritchle moved the starting point of the endurance rally to Lincoln, Nebraska because of the untenable lack of electrical infrastructure between there and Denver. He had a stock 1908 Fritchle Victoria Phaeton shipped to Lincoln. Fritchle departed from Lincoln at 7:30 a.m. of Oct. 31, 1908.

His route followed existing railroads as much as possible. Roads were still developing and were often maintained by localities, with no commonality of design and signage. Staying close to the railroads was a wise navigational aid in the day. From Lincoln he made his way to Chicago, getting lost on several occasions, then southward to Indiana and into Ohio. The farther east he drove, the better the roads were.

After spending the night in Toledo, Fritchle drove southeast until he arrived in very familiar surroundings, Wooster, arriving late in the evening of Nov. 15. He checked in at the Archer Hotel and slept while his car was charging. The trip from Toledo to Wooster was the longest of his entire journey, roughly 125 miles.

The following day he continued on his trip. He couldn’t resist the opportunity to drop by his brother’s home in Mt. Hope, reminiscing with family while he topped off the batteries of his Victoria Phaeton. Then it was on to Pittsburgh.

Fritchle arrived in Pittsburgh on Nov. 17, spending the night there. On the 25th he was in Gettysburg and took time to tour the infamous battlefield.

He arrived at the Knickerbocker Hotel in New York, New York on Nov. 28, 1908, officially completing his self-imposed challenge. But he wasn’t finished just yet.

He decided to travel from New York to Washington, D.C. in an effort to put his company and his vehicle in the national spotlight, arriving there on Dec. 10.

Fritchle returned to Denver by train. The following year he was back in Chicago at the automobile show held there. He continuously pressed the functionality and benefit of electric vehicles. In 1916 Fritchle marketed a gasoline-electric hybrid automobile.

In the end his company folded, acquiescing to the availability of gasoline and the superior range of gasoline-operated vehicles. He moved to Long Beach, California and operated a radio repair business out of his home. He died in relative obscurity on Aug. 15, 1951, and is buried there.