How Wayne County Congressional Medal of Honor winner earned it

William J. Knight was born in Wayne County’s East Union Township on Jan. 24, 1837, to Mr. and Mrs. Matthew Knight. Tragically, both of his parents were dead by the time he was age 5, and he was raised by his grandfather, Jacob Knight, in Defiance County. He worked there at his grandfather's sawmill, where he gained mechanical knowledge and how to work with steam-powered equipment.

On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces began shelling Fort Sumter, the beginning of the Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to quell the revolution and William Knight answered that call on Aug. 29, 1861, at the age of 24, enlisting in Company E, 21st Ohio Volunteer Infantry in Defiance.

The skills Knight brought with him to the Army led to him being used as a “sapper” — a combat engineer — building roads and bridges and performing other combat-related functions.

Although one of the states that seceded from the Union, Tennessee was a split state with many of its citizens remaining loyal to the Stars and Stripes. This was especially true in Eastern Tennessee.

Lincoln knew of this and wanted to take advantage of the Union's foothold there. A plan was unfolding to put a relatively unknown Union spy, James Andrews, in charge of a group of soldiers and civilians to sneak behind enemy lines, masquerading as civilians to travel south in small groups, meeting up in Marietta, Georgia on a mission to create mayhem and chaos on their return trip, aboard a stolen train.

It was decided to pull men from Col. Joshua Sill's brigade from the 2nd, 21st and 33rd Ohio Regiments. Andrews demanded at least three of the men have some experience with steam power. As a result, Cpl. Martin Jones Hawkins, Private Wilson Brown and Private William J. Knight became part of the team.

The entire team met for the first time on April 7, 1862. They were broken up in groups to travel to Chattanooga, and there, on April 11, they would board a train to Marietta. Andrews’ Raiders were born.

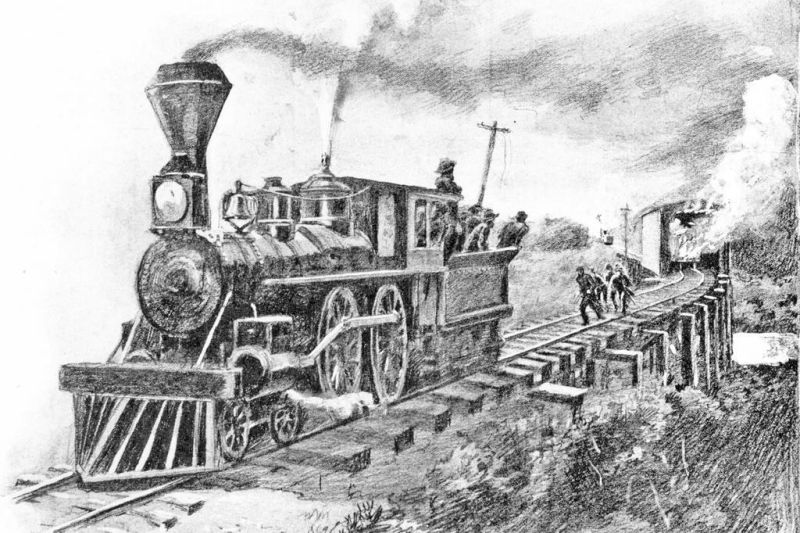

They would board a northbound train at Marietta. The locomotive for that train was famously known as “General.” They would be passengers until the train's breakfast stop in Big Shanty. Once all passengers and crew were inside the Lacy Hotel, enjoying their breakfast, the Raiders would uncouple the passenger cars and steal the locomotive, moving northward, destroying rails, bridges and telegraph lines as they went.

The ride north from Marietta was uneventful, and the train stopped in Big Shanty, as scheduled. Passengers and crew made their way to the adjacent motel — minus 20 men who were busy uncoupling cars and preparing the locomotive, tender and three box cars for the remainder of the mission. If all went well, the train and the pirates who stole it would be in Chattanooga in a few hours with a line of destruction behind them.

Hawkins, being the most experienced engineer, was supposed to act in that role for General's move northward, but he and Porter had overslept and missed the movement entirely. Control of the locomotive was handed to Knight.

With all passenger cars uncoupled, the men jumped into the boxcars, and the train began to move forward. Andrews’ Raiders were on the move.

The noise created drew attention of the crew and passengers, and three men gave chase on foot. A fourth man mounted his horse to head to the nearest telegraph station in Marietta to spread the word of the stolen train.

While they were gaining speed, the Raiders took out telegraph wires, using the momentum of the locomotive. All the while, the three pursuers were able to stay surprisingly close. Trains on that route averaged 15-20 MPH, and given that plans were to stop from time to time to destroy rail infrastructure, it's not surprising the pursuers were never far away. To make matters worse for the Raiders, the pursuers eventually acquired a hand car, which increased their speed.

The General proceeded northward, and upon arriving at Kingston, got held up waiting for three southbound trains to pass before they could resume their trek. By this time, the pursuers had acquired a locomotive of their own.

After stopping twice to cut wires and damage track, the Raiders arrived at Adairsville, where another delay awaited and the General sat beside a southbound train, the Texas, before getting under way again.

The pursuers came to the damaged track and were forced to continue on foot, but eventually came upon the southbound Texas and convinced its crew to pursue the General, in reverse.

Andrews’ Raiders stopped to inflict more damage, but before they could do so, they saw the Texas approaching, panicked, and resumed their journey. The Texas dropped a man at a telegraph station and notified Confederate forces to the north of the situation.

Just past Ringgold and low on fuel, the General finally had to stop. The order was given to abandon the train and scatter, every man for himself, to make it back to the Union line. Within a few days, all of Andrews’ Raiders were captured and jailed in Chattanooga to await trial.

Andrews was the first to be tried for spying. He was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. The execution came on June 11, and a week later seven more Raiders were executed in Atlanta.

The remaining 14 Raiders, having appealed to the Confederates for leniency and getting no response, decided to attempt to escape prison. On Oct. 16, a group of them overpowered guards, freed the rest of their comrades and a few other Union prisoners, and escaped. Six of them were recaptured, but eight, including Knight, made it back to Union lines and were reunited with their units. The six men that were recaptured were eventually returned to their units as part of a prisoner swap.

All 14 surviving Raiders served out the remainder of the war, and all survived it. On March 25, 1863, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton awarded six of them the very first Congressional Medals of Honor in the history of the United States. Nine more were awarded in September, 1863 including one to Knight, making him the only person with Wayne County connections to ever be given that award.

Knight returned to his life in Williams County following the war. He continued to work in the railroad industry and often lectured on his Civil War adventure. He died Sept. 26, 1916, and is buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Stryker, Ohio.

Mike Franks was raised in Apple Creek and has lived in Wooster most of his life. A retired engineer, he developed an interest in local history and enjoys writing about his discoveries.