With collection, Ron Coppa left slices of Orrville history

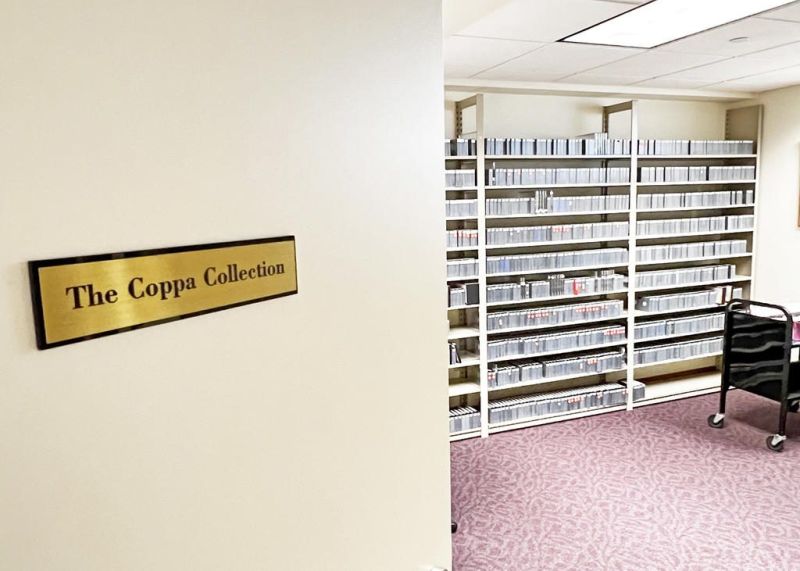

Like a miniature Blockbuster store with a narrower focus and nicer employees, a small room behind two locked doors on the lower level of the Orrville Public Library houses almost a century of history in video form.

Nearly 1,500 VHS tapes, many DVDs and sundry other items pack the shelves in the oversized closet with the door bearing the inscription: “The Coppa Collection.”

Ron Coppa arrived in Orrville in 1979 and started taking his own camera to high school football games and later other events in the mid-1980s. Yet material on the VHS tapes dates to the 1930s.

After collecting hundreds of old game films and other things in metal canisters, Coppa spent three years transferring them to VHS tapes, using his own cash to finance the necessary equipment.

“I also think sometimes they were showing a reel (on a screen) and someone was just recording it with a VHS camera,” said Dawn Geiser, the library’s teen service specialist and reference technician, who is very familiar with Coppa’s collection and the task the library faces when it comes to taking the videos to the next generation.

In other words, at some time in the process, Coppa — or someone — was filming films. Luckily, the process has become easier from an equipment standpoint but no less daunting where time and work are concerned.

The goal is to digitize the tapes. It’s an arduous task because there’s no easy way to do it. Cassettes are put in a machine and run at normal speed while a digital copy is produced.

So that’s hundreds of videos — many already have gone through the process — at 90 minutes to three hours apiece. It took Coppa three years to do the last transfer, and this time there are many more videos and perhaps far less available time.

The library started the conversion process nearly a decade ago, but transfers are only done when a particular need arises. As Library Director Daphne Silchuk-Ashcraft pointed out, VHS tapes do not have infinite shelf lives, so getting them done sooner rather than later needs to be a priority.

“When we were given this collection (in 2002), the hope was that we would let people come in and borrow them,” she said. “At that point I don’t even know if they were thinking about digitizing all of this. Now we’re putting them on to thumb drives. We’d like to have some cloud space at some point, but we don’t have it right now.”

Once digitized, a further goal may be to make the collection, which will be backed up on hard drives, streamable so it can eventually be accessed by anyone, anywhere.

For now, though, Silchuk-Ashcraft would just like to get more eyes on the videos. She estimates only about a half-dozen people a week visit the collection.

“Hardly any,” she said. “I’m sure people don’t know we have it. We need to start promoting it.”

Silchuk-Ashcraft had been at the library for about five years or so when she got her first glimpse of how important the Coppa videos are.

“My first memory of it was when two men, elderly men, one from Wooster and one from Orrville, said, ‘We heard you have the tape from this game,’” she said. “I couldn’t tell you which game. It was from like 1960, 1964. So we got it out. We had a TV with a VHS player underneath it, and we got the tape and put it in, and they sat there and watched that. They knew all the people. That’s when I felt this was very important.”

Silchuk-Ashcraft said the video quality of many of the tapes is not great, and a lot of them have no sound. Though Coppa added music to some, there’s no announcer on the football tapes, for example, saying who carried the ball or what the score is.

That, however, is not the point. The videos are live documentations of history. The tapes fill in gaps that newspaper archives — which are shrinking themselves — have never been able to fill.

“Those men watching that football game were just so thrilled to watch that,” Silchuk-Ashcraft said. “They both asked us at that time to make a copy. We were first charging like 10 bucks to make one. We’re not doing that now.”

Coppa, a 24-year veteran of the United States Navy, died in 2015. His most recent videos were from about five years prior.

Silchuk-Ashcraft said there may be a bit of a gap in the town’s video history starting around a decade ago, but with everyone toting around smartphones now, people have their own video collections.

In a perfect world, she said, people would share some of the most significant videos with libraries — in all towns, not just Orrville — to keep a running record of towns’ histories for future generations to see or just for older generations reminiscing.

“It is a wealth of information,” Silchuk-Ashcraft said. “It’s interesting and kind of fun. The ones that have plays and shows and things like that, when you can see people’s faces, are so much fun. It’s just interesting to see how the town has changed. One of the parades, they had an oxen pulling a wagon. Who does that in parades now?”

Coppa’s collection now remains static with no wiggle room for interpretation.

“I wish I’d have gotten a chance to talk to him, and I never did,” Silchuk-Ashcraft said. “That would have been an interesting conversation. There’s a lot of things I’d like to have asked him.”